Methadone clinics in New Haven – a diary

Part 1

By Tom Goldenberg, Democratic candidate for Mayor of New Haven

This is part of a series where Democratic Mayoral candidate Tom Goldenberg highlights his first-hand experiences with New Haven’s methadone clinics and explores what a new model could look like.

The question came from a friend of mine who was concerned about the quality of life in New Haven neighborhoods like The Hill and Newhallville – what should the city do about the methadone clinics? I recently read an article by the New York Times on harm reduction efforts in New York City that highlighted both the pros and the cons of safe-use sites. On the one hand, there was a positive case for making a difference in the lives of people on the brink of overdosing. On the other, such sites were often opened in underserved communities of color (such as East Harlem) despite demand being higher outside of those communities. I had also heard from multiple sources that the City of New Haven and Yale were considering opening safe-use sites. There seemed to be a conflict between the aims of public health and the fairness of economic justice, and this resonated with the discussions I had heard about methadone clinics as well.

I talked about this to my wife, Dr. Jessica Holzer, a public health Professor at the University of New Haven. She was able to explain to me how methadone is used to provide long-term treatment to opioid-addicted patients, most of whom are able to lead productive lives at work through the treatment. If there was a problem with methadone clinics in New Haven, as had been reported by many people, it wasn’t with the science of methadone treatment. I would have to go myself and observe what people were complaining about. And I would start with the location that has gotten the most criticism – 495 Congress Avenue.

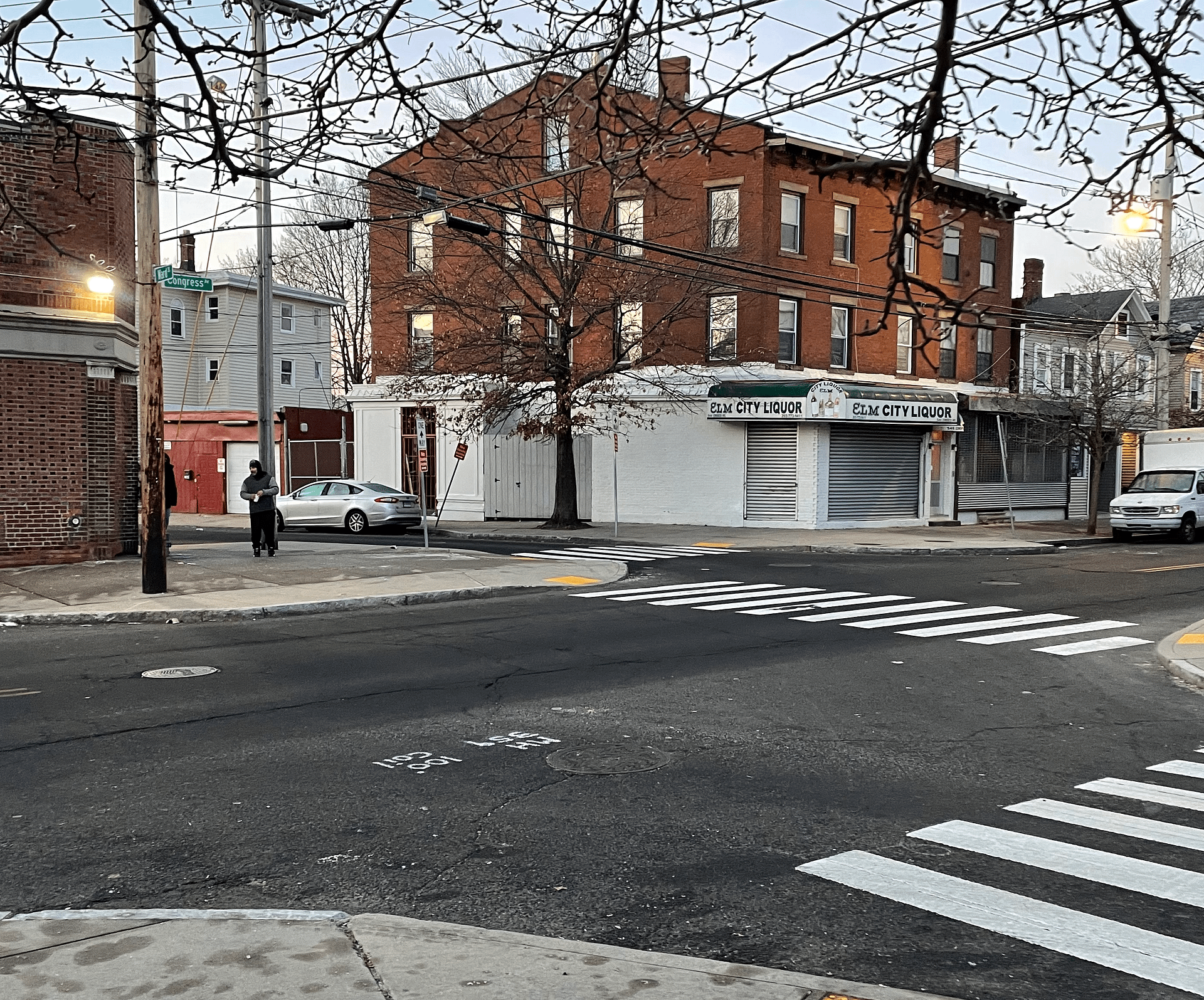

On Monday, February 27, at around 6 am, I drove to the APT Foundation methadone clinic on Congress Avenue. I was dressed in a sweater and windbreaker pants. I got out and walked among a group of five or six people who were hanging out. “Want bottles?” a woman asked, to which I simply shook my head. I walked around the block to get the lay of the land, as the sun was starting to peak out, then I approached the same woman. I learned that she was originally from New Milford, used to live in Waterbury, and moved to New Haven to be close to the clinic about five years ago when she started methadone. “It works great,” she told me.

My campaign field director Jayuan Carter arrived a little later than me. We sparked the interest of a man dressed in all black and a baseball cap who called himself “Ghost.” It seemed clear to us that he was dealing drugs, as we saw him make exchanges with cars that pulled up intermittently. “I got bottles if you need ‘em,” I overheard him say on the phone. I wondered what was in these bottles? Jayuan and I struck up a conversation with Ghost, explaining that simply wanted to understand more about the clinic and how it might affect the Newhallville neighborhood, where APT had purchased a property. “This is the Devil’s asshole,” he said. If APT opened up there, “the neighborhood will go to shit.” He said that he appreciated how we were trying to take care of the neighborhood.

As he scanned around the area, which was by now much more crowded, he told us that people mostly sold crack in front of the APT building, although there were also “benzos,” and heroin. “Need bottles?” I heard again, while I glanced across the street at John Daniels school. It was almost 7 am, school would be starting soon. On the other side of the building were apartments, each one with a “No loitering or trespassing” sign.

Ghost took an interest in us and explained what went on at the clinic. He showed us a corner of the building exit ramp where he said people camped out and did crack at night. He estimated that people defecated outside two or three times a day and that there were 2-3 fights a week. He shared how he himself “punched the shit out of” someone last week. But fights were “bad for business.”

Why was it that this location had so many issues? “This is the most lenient clinic,” Ghost said. Other locations didn’t have the same problems. He also said that a majority of patients come from outside of New Haven. He suggested I check out the Cornell Scott Hill Health site next. Or “Benzo alley” by the Rite Aid. “But be careful and don’t trust anyone.” He ended by telling us that the Congress Avenue location was like a “powder keg” – two “capos” had recently disappeared, a phrase that immediately called to mind the Sopranos. The entire scene seemed like it was out of the T.V. show The Wire. Before getting back in my car to go home, I walked around the block, where I saw groups of young kids going to school, the sun fully overhead.

DONATE to Tom’s Mayoral campaign

Part 2

By Tom Goldenberg, Democratic candidate for Mayor of New Haven

This is part of a series where Democratic Mayoral candidate Tom Goldenberg highlights his first-hand experiences with New Haven’s methadone clinics and explores what a new model could look like

Yesterday I visited the APT Foundation site at 495 Congress Avenue. Today was a snow day, so missed the opportunity to see the opening of another clinic. That would have to wait a day. Today I wanted to know how residents felt about the Congress Avenue clinic, so I would knock on doors to find out.

I started at the end of Congress Avenue, where the street connects with Davenport Avenue and both streets merge with Columbus Avenue. While this area was three blocks from the APT Foundation site, I still heard a lot of complaints about the clinic. At one house, when asked about the methadone clinic, a mother told me from her porch, “It’s gotta go!” Then she asked her sister and 19-year-old daughter to come and tell me the same. The sentiment was the same in most of the doors I knocked on, expressed with either enthusiasm or resignation.

Moving closer to the clinic, I asked a passerby what he thought about the clinic. He asked to be anonymous and said that the clinic “exacerbated local issues,” such as crime and cleanliness. He told me that he would regularly find used needles and drugs. “This isn’t a good place for kids.” John Daniels school stood right to our left, and immediately beyond that was the methadone clinic.

Not everyone believed that the clinic was at fault. One young man that we spoke to told us that “a lot of people are hurting.” Moving the clinic somewhere else just “feels like a band-aid” without addressing the lack of a social safety net that we have in this country. When I spoke on the phone to a local elected official, he also disagreed that the clinic is at fault. He told me forcefully, “there isn’t an issue with the clinic.” After warning me not to cause trouble, he hung up the phone.

I got closer to the APT building on Congress Avenue. I found a police car out front so I talked to the officer. I asked about drug dealing. “There’s nothing we can do,” he said. The city has a no-prosecution mandate for drugs, so if they arrest people they just immediately let them go. The city started a program called LEAD that offers users rehabilitation or arrest, but “they always choose arrest because they know they’ll just be let go.”

What about collaboration with APT? “They don’t like us,” he said. APT was forced to have some police presence after a murder in their driveway a few years ago. But they generally complain that “clients don’t feel safe” when police are there. They let people encamp on the property and do drugs, which “we can’t police because it’s private property.”

Why was this location so problematic, when other methadone clinics in and near New Haven didn’t report such quality-of-life issues? I was planning on visiting more clinics the next day, including ones in West Haven and on the Long Wharf. I also wanted to speak to APT staff to understand more about the organization’s decisions from site to site. Hopefully, this would lead to some answers.

DONATE to Tom’s Mayoral campaign

Part 3

By Tom Goldenberg, Democratic candidate for Mayor of New Haven

This is part of a series where Democratic Mayoral candidate Tom Goldenberg highlights his first-hand experiences with New Haven’s methadone clinics and explores what a new model could look like

After visiting the methadone clinic run by APT Foundation on Congress Avenue, the clinic at 185 Front Avenue in West Haven was like a breath of fresh air. As I pulled into the parking lot at the back of the building, the sun was starting to rise. There were no drug dealers in front, no visible quality of life issues. Across the street were a few scrap yards and no immediately visible residences.

Inside the atmosphere was calm and orderly. I spoke to an employee there. I asked him why the Congress Avenue location had quality of life issues that this clinic doesn’t have. “This population is more stable,” he said. One patient recently came from the Congress Avenue location and was amazed at how much better this one is. I remembered how the Congress Avenue location was right across from a school and a residential neighborhood.

So why don’t people just come here? “Some people don’t want to be stable, you know what I mean?” The employee also said that the Congress Avenue clinic is more lenient, something the patients and drug dealers had told me as well. The Front Avenue location turns away clients who fail drug tests, but the Congress Avenue location does not, he explained.

As for the drug dealers? “If you scalp tickets, you hang out at the football stadium.”

Next I drove to the 1 Long Wharf Drive APT Foundation. The sun was fully overhead by now. I looked around here and saw no residences either. No loitering or drug dealing. Inside, the atmosphere was quiet and the staff was friendly.

I called Ghost (a drug dealer I met on the first day) and asked if he would be willing to do an interview on the issues of the Congress Avenue location. “I’m afraid of getting whacked,” he said. “People make a lot of money off of this.” But he felt like he had an obligation to tell his story. He just needed time to decide.

That afternoon I read past articles about the APT Foundation. How they testified to the New Haven Board of Alders in 2018 after a murder and when they were questioned on quality of life issues on Congress Avenue. I also read about how they purchased a building in Newhallville, another Black residential neighborhood, for $2.4M. The amazing thing was that the Mayor and his administration did nothing to inform that community, including not notifying the local elected official, Alder Devin Avshalom-Smith. When criticized for this, Mayor Elicker said that City Hall had “encouraged” APT to reach out to the community, which they did not do.

Now I could see why people were upset. The issue wasn’t about the methadone treatment. It was about respect for communities of color. Clearly, there were well-run clinics that did not have drug dealing or quality of life issues. The Congress Avenue facility was either poorly located or poorly managed, but I needed more information to come to a conclusion as to what the city should do about it.

DONATE to Tom’s Mayoral campaign

Part 4

By Tom Goldenberg, Democratic candidate for Mayor of New Haven

This is part of a series where Democratic Mayoral candidate Tom Goldenberg highlights his first-hand experiences with New Haven’s methadone clinics and explores what a new model could look like

After having visited APT Foundation sites on Congress Avenue, Front Avenue in West Haven, and 1 Long Wharf Drive, I visited the Cornell Scott Hill Health methadone clinic on Cedar Street. This clinic opens at 8:30 am, so I was able to drop off my daughter at school before driving over to the site. I pulled up around 8:45 am and went inside. There was a busy line and a somewhat tense atmosphere. A police car was stationed in front and there were three security guards at the front entrance. It appeared that some incident may have happened earlier. I asked to speak to a supervisor but instead was handed a pamphlet and told to call later.

I was able to speak to the officer stationed outside. I asked if he had any indication about the demographics of the patients. He said that it was a majority from outside New Haven, from his experience. He said that police only came when there were complaints.

I scanned the area outside of the clinic. It was industrial on one side – a large parking lot and a hospital building. But the other side was residential apartments, many that were blighted, along with the Boys & Girls Club building, and a block away, St. Martin de Porres school.

I then walked over to the Congress Avenue APT Foundation location. On the way, I saw a man dressed in black sweats and a hoodie pulled over his face and his hands in a position that looked like he had just injected heroin. He was sitting on a bus bench. Across from the APT site, I said hello to a construction worker and a security guard. They shared stories of breaking up fights in front of the building.

I then drove to the Dixwell property that APT bought for $2.4M, which the Mayor and his administration didn’t even notify the local community about. It was a gorgeous building with the words inscribed above the entrance – “For God and for country,” like a motto that predated the Yale one. The former school was near several businesses on Dixwell Avenue, including a wings joint, and behind it was a residential neighborhood. I walked around the block and met a woman walking a dog. I asked her how she felt about the plans to open a methadone clinic. “I hadn’t really thought about that,” she said. “I thought it would take years to happen.” She might be right, I thought.

I was also able to speak with a community activist in Newhallville who opposed the opening of APT in the Dixwell Avenue location. We talked about the need to call for economic justice but without stigmatizing those with opioid addiction or disrespecting the science of methadone treatment. We felt that we could honor the mission of public health but also call for economic justice in communities of color – by enforcing methadone clinics to be in industrial-zoned areas. This would include calling for the relocation of the 495 Congress Avenue clinic and for the sale of the Dixwell Avenue site that was purchased by APT. Although our conversation went well, we knew there was more work to do. Somehow, we had to align these two groups – public health advocates and activists for communities of color.

DONATE to Tom’s Mayoral campaign

Part 5

By Tom Goldenberg, Democratic candidate for Mayor of New Haven

This is part of a five part series where Democratic Mayoral candidate Tom Goldenberg highlights his first-hand experiences with New Haven’s methadone clinics and explores what a new model could look like

As I mentioned earlier in this series, my wife is a public health professor. We frequently have vigorous debates on a variety of topics, and this topic was no different. I was calling for a new approach to the placement of methadone clinics. What would the public health ramifications of this be?

This morning we both got up early to visit some of the methadone clinics. We drove first to Congress Avenue. As we stepped out, at around 6 am, it felt quieter than the last few times I had been there. I walked Jess around the block, showing the John Daniels school and then the residential apartments nearby.

On our way back around, we encountered two people, one of whom asked us if we wanted drugs. When we explained that we were just looking to understand more about the clinic to see how it might affect a neighborhood like Newhallville. The one who asked if we wanted drugs, Meg, said, “it definitely would not be good for that neighborhood.” She explained that people mostly sold crack and benzos in front of APT, though also heroin and weed.

The Congress Avenue location was “by far the most lenient.” They “still give COVID bottles even if you’re dirty,” which meant that you didn’t need to pass a drug test. No other clinic did that.

We decided to go inside and speak to someone from APT. We were able to speak to an employee outside. I explained what we were interested in and asked about the demographics of the client population. “I don’t want to say anything that would get me in trouble,” he said, so he told us to follow up with his superior.

We then walked to the Cornell Scott Hill Health site, and then we drove to the Dixwell Avenue building that APT bought and that the community had been protesting. We discussed some of the challenges in this scenario. It is difficult to draw direct causation between a methadone clinic and quality of life issues. I’m not sure if any researchers have done this. But our observations do show that some methadone clinics operate much better than others. Those that are in industrial zones have fewer issues with drug dealers or other quality of life issues.

Would removing the methadone clinics from residential areas solve all of the quality of life problems? There would have to be a plan to then use the freed-up building for positive economic use. There would have to be sufficient transportation to the available sites utilizing Veyo and the bus system.

And yet, it did seem like the start of economic justice for these communities. The methadone clinics were not ill-intentioned. They wanted to improve peoples’ lives, and certainly did so. But that needn’t be at the cost of poor Black and Brown neighborhoods. As a city, we can plan better. This is why we call for zoning that mandates methadone clinics to be in industrial areas. In the meantime, the clinic with the most quality of life issues should not be the “most lenient.” All efforts should be made to ensure that the Dixwell Avenue site is not used for a clinic. And a plan should be put in place to transition APT from Congress Avenue to an industrial-zoned area.

We can have both – economic justice and public health. It just requires us to work together.